Avoid blocking calls in a cache using Java

In this post, we are going to talk about caches, the importance that they have, the issues with blocking operations, how to detect slow operations in your API, and an example of implementing a nonblocking cache in Java with the Guava library.

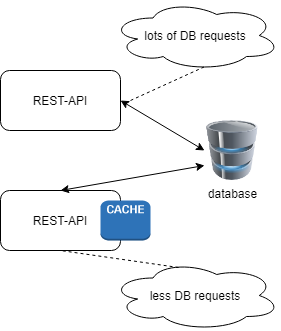

Advantages of a cache

A cache in computing helps your system to avoid repeated expensive operations that the result of this computation doesn’t change and that repeated requests should send the same results to a client.

A cache typically holds values in a key-value way that allows fast access to the result of the computation. Given a key, you can retrieve the result associated with this key in constant time (aka O(1) time).

If your system needs data from another system (database, rest-API) and the data received in the response doesn’t change often you should use a cache to reduce response time and avoid expensive calls.

Blocking input/output (I/O)

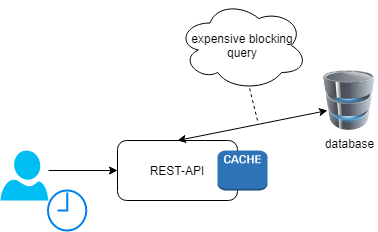

Having a cache is a good thing but we have to be careful about how the data in the cache is populated. To understand the problems that can arise from populating data into the cache we have to understand the concept of blocking I/O operations.

Typical blocking I/O operations:

- Reading/writing a file from the filesystem

- Making a query to the database

- Calling a rest service API

Blocking I/O means that a given thread cannot do anything more until the I/O response is fully received. Non-blocking I/O means an I/O request is queued straight away and the function returns. The actual I/O is then processed at some later point.

If your application is doing this kind of operations and the clients of your operation have to wait until this time-consuming operation finishes, you are blocking them to receive a response in a reasonable amount of time.

Detecting slow operations in your API

One way to detect slow method calls in your backend endpoint is to use metrics to measure the amount of time that a particular operation is consuming. You can send metrics to InfluxDB and draw those metrics using Grafana dashboard.

Another option is to do a call before calling a method to

public static long currentTimeMillis() to calculate the number of miliseconds that the suspicious method is consuming in time.

long time1 = System.currentTimeMillis();

List<Book> books = booksService.loadAllBooks();

long time2 = System.currentTimeMillis();

System.out.println("Method loadAllBooks spends: "+(time2-time1));

This is something to use in your local machine when you are investigating if some method is consuming a lot of time. I would use the option to send metrics to InfluxDB if I want to monitor in production some method is spending a lot of time, in particular calls to API methods that I don’t have control.

Reloading data into caches

Let’s say that your API needs to call a second API to retrieve information regarding geographic information. This geographical information if it doesn’t change during time is a candidate to load it into a cache of your API to avoid calling multiple times to the service and also to avoid blocking the caller of your API waiting for a response can be preloaded in the cache.

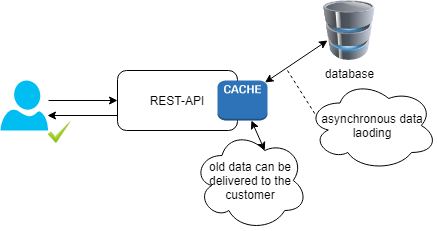

But what if the information that we have in this cache changes over time? what if we need to reload these values of the cache every 15 minutes because we have updates in the information that we are using? If we have a tool where the users can update data and because of that we need to reload the caches of our API? When a client calls an endpoint should they wait until all the data is loaded again in the cache to receive the response?

Here is when Guava java library can help us to loading data into the cache asynchronously without blocking the clients of the API.

A non-blocking cache implementation

Guava java library has an interface LoadingCache that has methods related with cache. The library also provides a CacheBuilder whose constructor needs a CacheLoader that has different methods to load values into the cache. In the following example we have implemented the loadAll method from CacheLoader to retrieve all books from an external service.

In the following code we can see how to implement a cache using Guava library in collaboration with ScheduledExecutorService

import com.google.common.cache.CacheLoader;

import java.util.HashMap;

import java.util.Map;

public class BooksCacheLoader extends CacheLoader<Long, Book> {

public Map<Long, Book> loadAll() {

//expensive query that loads all values.

}

@Override

public Book load(Long aLong){

// query that returns the Book from an id

}

}

import com.google.common.cache.CacheBuilder;

import com.google.common.cache.LoadingCache;

import java.time.Duration;

import java.util.Map;

import java.util.concurrent.Executors;

import java.util.concurrent.ScheduledExecutorService;

import java.util.concurrent.TimeUnit;

...

BooksCacheLoader cacheLoader = new BooksCacheLoader();

LoadingCache<Long, Book> booksCache = CacheBuilder.newBuilder()

.maximumSize(10000)

.expireAfterWrite(Duration.ofMinutes(30))

.build(cacheLoader);

ScheduledExecutorService scheduler = Executors.newScheduledThreadPool(1);

scheduler.scheduleAtFixedRate(() -> {

Map<Long, Book> map = cacheLoader.loadAll();

booksCache.putAll(map);

}, 30, 30, TimeUnit.MINUTES);

With the previous code we will load into the cache the books that we have retrieved from the database every 30 minutes. with the help of ScheduledExecutorService and scheduleAtFixedRate we can reload the values and we don’t block clients of our rest-API even that the query to the database is time expensive.

Conclusion

In this post we have talked about caches, blocking I/O operations, reloading data into caches and we have seen an example of how Guava can help to implement a cache.

Comments